Portrait of Cristobal Riestra. Courtesy of OMR. Portrait of Cristobal Riestra. Courtesy of OMR.

“You’re involved because you were born into it,” Cristobal Riestra told Artsy, speaking on his lifelong journey with OMR, the Mexico City gallery his parents founded in 1983—the same year he was born. All his life, Riestra grew up in an environment saturated with art and populated by artists. For him, the gallery served as both a home and classroom, shaping his understanding and appreciation of the art world from a young age; this upbringing would naturally pave the way for him to carry on the torch at OMR.

Running a gallery is frequently a family affair, and recent years have seen a wave of succession take place across the art world. Blue-chip galleries such as Pace Gallery, Lisson, David Zwirner, and Almine Rech are among those to have handed over a form of stewardship to the next generation. This transition phase, marked by both continuity and innovation, often holds the potential to reshape the fabric of these galleries. But how do family dynamics influence the professional lineage?

Eduardo Sarabia, installation view of “Four Minutes of Darkness” at OMR, 2024. Photo by Ramiro Chaves. Courtesy of the artist and OMR, Mexico City.

In 2016, Riestra officially took the helm of OMR following the early retirement of his parents, Patricia Ortiz Monasterio and Jaime Riestra. Today, the 40-year-old gallerist acknowledges the dual influences of his parents: His father’s creativity and flair for curating engaging exhibitions inspired Riestra to push the boundaries of art presentation, moving away from the densely packed displays of the 1980s to a more curated, modern aesthetic. Meanwhile, his mother’s meticulous attention to detail and openness to diverse practices instilled in him a broad-minded approach to art curation. “From my mother and my father because they each contributed a different value, and now that I’m running it, I have to do both,” he said.

But the transition to leadership was not without its challenges. Riestra and his parents experienced periods of misalignment, leading them to seek external assistance. This pivotal time, however, allowed Riestra and his parents to reassess the direction of the gallery.

“After some time of struggle, where we were not particularly aligned, it felt like an uphill battle constantly,” Riestra shared.

Portrait of Lauren Kelly by Sarah Muehlbauer, 2018. Courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

“My parents were a bit tired, and there was conflict about the way things were done. I think that’s common in second-generational businesses, so we hired a consulting firm that specializes in transitions for family businesses from one generation to the next. That was great,” he recalled. “It was like having a therapist—a family therapist—that allows you to separate the emotional part of it, to create a clear structure and a clear way of doing things, and to understand the value of the brand and what needs to be rescued and what could change.”

Similar to Riestra’s experience, Lauren Kelly, daughter of Sean Kelly and director of Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, also acknowledges the complexities and rewards of working within a family-run gallery. She notes that disagreements can feel different when they come from a family member.

“It’s different for your colleague to say they don’t agree with your opinion than your father to say that he doesn’t agree with your opinion,” Kelly said. “Even though it’s always done professionally, it still can feel different. I’ve had to, with age, be able to understand and just remind myself that this is a professional opinion, and I have to be treated as my other colleagues would be treated in that. And so, with age and maturity, it’s really helped to be able to establish that boundary.”

Hugo McCloud, disclosed fluidity, 2023. Courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

When Kelly started at the gallery as a 22-year-old assistant, her father had her work under the gallery’s long-time executive director Cecile Panzieri to help navigate the intricacies of familial and professional dynamics. This strategic decision allowed Lauren to forge her own independent path within the gallery. Kelly noted that her personal work with American artist Hugo McCloud truly anchored her decision to stay in the field. “Seeing how fulfilling my life could be through helping and facilitating his career growth—that was like a point where I said, ‘I want to do this forever,’” she said.

Kelly’s brother, Tom, also followed their father’s legacy. After officially joining the gallery in 2011, he helped usher in its first West Coast location in 2023. Together, the Kelly family has created a structure where all three tackle the business with their strong suits.

“We have really created a network to be able to understand and to be a resource to each other,” Lauren said. “It’s complicated, but it’s also more rewarding when we’re successful, and we mount an exhibition that we’re proud of, or we do a good job for one of our artists—I get to celebrate my family.”

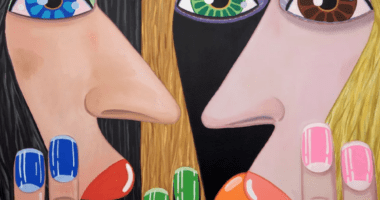

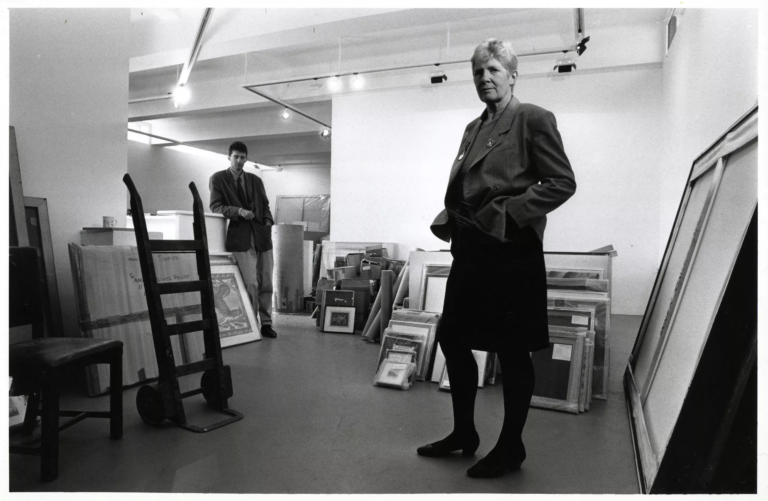

Portrait of Matthew and Angela Flowers by Frank Herrman, 1988. Courtesy of Flowers Gallery Archive.Hugo McCloud, disclosed fluidity, 2023. Courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Meanwhile, Matthew Flowers—now 67 years old—worked closely with his mother, Angela Flowers, for nearly 50 years at London’s Flowers Gallery before she passed away in 2023. Flowers’s story starts at 13 years old, when he started helping out on Saturday mornings. After a stint as a musician, he returned to the gallery, helping his mother operate its London space and open Los Angeles and New York City outposts.

“I felt she gave me the confidence to do my own looking,” Flowers said. “What she passed on really is how important the artists are—really having an interest in what they do and looking and not just using your ears and hearing who’s good or what’s fashionable, but training to look yourself and trust in your own judgment.”

Patrick Hughes, Rollei-Poly, 2010. Courtesy of Flowers.

From the onset, Flowers and his mother worked as a team, bouncing ideas and artists off one another. Flowers recounts he felt “very in tune” with his mother, a defining characteristic of the gallery and their exhibitions. Together, the Flowers family created what he believes is their greatest concept exhibition: “Artist of the Day.” The series kicked off in the 1980s, and they would invite 10 well-known artists to select someone they thought could benefit from a one-day exhibition, running it for two weeks. These shows were hosted by artists including Maggi Hambling, Tom Phillips, and Patrick Hughes.

In Sweden, Johan Hauffman carries forward a legacy that spans three generations at Mollbrinks Gallery, a gallery founded by his grandfather, Lars Mollbrink, in 1957—two weeks after Hauffman was born. Now, alongside his father, Jan Mollbrink, Johan is at the helm, intertwining tradition with a modern approach. For him, the most significant change came after his grandfather passed him the baton.

“My father and I think the same thing,” he shared. “We want the same thing. We work the same way. We do the same thing, but my grandfather was more of a different generation.”

Portrait of Jan Mollbrink and Johan Hauffman holding Marc Chagall’s Le Bonheur du jeune couple aux fleaurs, 1967. Courtesy of Mollbrinks Gallery.

Despite these shifts, a common thread of dedication and passion for art runs through the family, ensuring the gallery’s continued relevance and success. However, Hauffman also acknowledges the challenges that come with adapting to changing tastes and market demands, a testament to the dynamic nature of the art world and the resilience required to thrive within it. “When [my grandfather] started, most people wanted to have decorations, and it wasn’t known artists and businesses,” he said. Instead, Hauffman started to focus more on the gallery’s relationships with the artists and how to curate an exhibition.

“That is a big difference between me and my grandpa, because he wanted as many paintings up on the walls as possible, every white spot on the wall,” Hauffman said. “But I wanted him to look at the possibilities.”

As these gallerists hand over their galleries to the next generation, being born into the art world evolves from mere circumstance to a deep-seated dedication to art, artists, and a family legacy. This shift often forces gallerists to navigate the complexities of family dynamics in the context of their professional roles. It is a world where the legacy of the past and the vision for the future come together.